Shortly after the death of Giorgione in the fall of 1510, Sebastiano Luciani and Tiziano Vecellio, the two young painters most likely to succeed him as the favorite of Venetian patrons, left Venice to pursue their careers elsewhere.

Sebastiano, later known as Sebastiano del Piombo, could not refuse the offer made him by the wealthy Sienese banker Agostino Chigi to work for him in Rome. One of the reasons why Chigi chose Sebastiano over Titian might have been the fact that the former was considered to be the superior painter.

In “Titian to 1518” Paul Joannides discussed Sebastiano’s standing in the ranks of Venetian painters.*

Joannides devoted considerable attention to this cycle that depicted three of the miracles attributed to St. Anthony of Padua, and did his best to point out traces of the skill that would characterize Titian’s later work. Nevertheless, if Titian had died after completing this cycle no one today would regard him as more than a second or third-rate painter.

After the completion of the Paduan cycle, Titian returned to Venice late in 1511 and, according to Joannides, decided to take his work to a new level.

In the next four years Titian would produce a remarkable series of oil paintings that raised him to the highest level. Joannides noted that these works are difficult to date precisely but I follow his probable dating. (Page numbers in parenthesis refer to "Titian to 1518")

“Pastoral Scene ('The Concert Champetre')” (probably 1511). Oil on canvas, 110 x 138 cm. Louvre. (99)

“Virgin and Child with Saints Anthony and Roch” (probably 1511). Oil on canvas, 92 x 133 cm. Madrid, Prado. (123)

“Virgin and Child (‘The Gypsy Madonna’)” (probably 1511. Oil on panel, 66 x 84 cm. Vienna. (141)

“The Virgin and Child” (‘The Bache Madonna’) (probably 1512). Oil on panel, 40 x 56 cm. NY, MMA. (144)

“Holy Family with an Adoring Shepherd” (probably 1512). Oil on canvas, 99 x 117 cm. London, NGA. (145)

“Saint Mark Enthroned with Saints Cosmas, Damian, Sebastian and Roch” (probably 1512). Oil on panel, 230 x 149 cm. Venice, Santa Maria della Salute. (149)

“Jacopo Pesaro Presented to Saint Peter by Pope Alexander VI” (probably 1513). Oil on canvas. 145 x 184 cm. Antwerp, Musee Royale des Beaux-Arts. (152)

“Unknown Donor Presented to the Virgin and Child by St. Dominic, with Saint Catherine Attendant” (probably 1513-14). Oil on canvas. 138 x 185 cm. Parma, Fondazione Magnum Rocca. (158)

“Rest on the Flight into Egypt” (probably 1512). Oil on (paper laid down on) panel, 46.3 x 61,5 cm. Longleat, Wiltshire, Marquess of Bath Collection (stolen 6 January 1995). (161)

“Tobias and the Angel Raphael” (probably 1514). Oil on panel, 179 x 146 cm. Venice, Accademia. (167)

“Baptism of Christ” (probably 1514). Oil on panel, 115 x 89 cm. Rome, Museo Capitolino. (172)

“Noli Me Tangere” (probably 1514). Oil on canvas, 109 x 91 cm. London, National Gallery. (173)

“Sacred and Profane Love” (probably 1515). Oil on canvas, 118 x 279 cm. Rome, Galleria Borghese. (186)

Titian: "Noli Me Tangere"

Titian: "Noli Me Tangere"

Joannides dealt with Titian’s portraits in a separate chapter but looking at the list above we must say that until Titian painted the “Sacred and Profane Love” in 1514-5, he was primarily a painter of “sacred” subjects.

The sole exception would be the controversial and mysterious “Pastoral Concert”: controversial because scholars still cannot agree on whether to give it to Titian or Giorgione, and mysterious because there is no agreement on the subject of the painting.

Moreover, Joannides noted Hourticq’s opinion that “although the ‘Concert’ was laid in by Titian around 1511, he completed it only around 1530…” He confessed that the temptation to accept Hourticq’s view is “considerable.” (p. 100)

In the five years after Giorgione’s death Titian became one of the greatest painters of the Renaissance but on the eve of the Reformation he and his patrons were still interested primarily in “sacred” subjects.

*Paul Joannides, "Titian to 1518" Yale,2001.

|

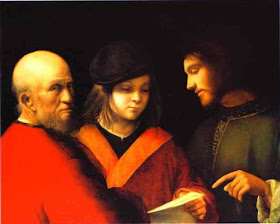

| Sebastiano del Piombo, organ shutters, Saint Louis of Toulouse and Sinibaldus. (probably 1510-11), oil on canvas, each 293 x 137 cm, Academia, Venice |

Sebastiano, later known as Sebastiano del Piombo, could not refuse the offer made him by the wealthy Sienese banker Agostino Chigi to work for him in Rome. One of the reasons why Chigi chose Sebastiano over Titian might have been the fact that the former was considered to be the superior painter.

In “Titian to 1518” Paul Joannides discussed Sebastiano’s standing in the ranks of Venetian painters.*

Sebastiano seems to have been further advanced in his career than Titian before mid-1511, and his work more controlled and mature….It is notable, and an inherent quality of Sebastiano's work, that he always possessed a more severe, solid and sculptural sense of form than either Giorgione or Titian, qualities that later attracted Michelangelo to him. (129)Whatever the reason for Sebastiano’s departure Titian was left with a practically open playing field. Only the aged but active Giovanni Bellini stood in his way. However, Titian decided to accept a commission to paint a fresco cycle in Padua’s Scuola del Santo. This commission, negotiated in December 1510, provides the first recorded documentary evidence of Titian’s existence.

None of his contemporaries bettered Sebastiano's organ shutters and it is worth pausing to consider what this implies. It seems certain that all three of the major paintings... were commissioned from Sebastiano before the death of Giorgione and, perhaps, against Titian. If so, it would imply that Sebastiano was widely seen as the leading young painter in Venice, in preference to either of the others. But why, if by 1511 Sebastiano was in so commanding a position, with Giorgione dead and with little to fear from Titian in major commissions, did he accept Agostino Chigi's invitation to Rome? (136)

Joannides devoted considerable attention to this cycle that depicted three of the miracles attributed to St. Anthony of Padua, and did his best to point out traces of the skill that would characterize Titian’s later work. Nevertheless, if Titian had died after completing this cycle no one today would regard him as more than a second or third-rate painter.

After the completion of the Paduan cycle, Titian returned to Venice late in 1511 and, according to Joannides, decided to take his work to a new level.

"A double effort was required: self-discipline and self-education. Self-discipline consisted largely in reduction: in attempting less within his paintings Titian was able to achieve more. Self-education made Titian a more effective figure-draughtsman. For self-discipline Titian looked to his great target, Giovanni Bellini, reconsidering the principles of his art; for self-education, he studied the art of Central Italy in a more intense and focused way than hitherto." (141)

In the next four years Titian would produce a remarkable series of oil paintings that raised him to the highest level. Joannides noted that these works are difficult to date precisely but I follow his probable dating. (Page numbers in parenthesis refer to "Titian to 1518")

“Pastoral Scene ('The Concert Champetre')” (probably 1511). Oil on canvas, 110 x 138 cm. Louvre. (99)

“Virgin and Child with Saints Anthony and Roch” (probably 1511). Oil on canvas, 92 x 133 cm. Madrid, Prado. (123)

“Virgin and Child (‘The Gypsy Madonna’)” (probably 1511. Oil on panel, 66 x 84 cm. Vienna. (141)

“The Virgin and Child” (‘The Bache Madonna’) (probably 1512). Oil on panel, 40 x 56 cm. NY, MMA. (144)

“Holy Family with an Adoring Shepherd” (probably 1512). Oil on canvas, 99 x 117 cm. London, NGA. (145)

“Saint Mark Enthroned with Saints Cosmas, Damian, Sebastian and Roch” (probably 1512). Oil on panel, 230 x 149 cm. Venice, Santa Maria della Salute. (149)

“Jacopo Pesaro Presented to Saint Peter by Pope Alexander VI” (probably 1513). Oil on canvas. 145 x 184 cm. Antwerp, Musee Royale des Beaux-Arts. (152)

“Unknown Donor Presented to the Virgin and Child by St. Dominic, with Saint Catherine Attendant” (probably 1513-14). Oil on canvas. 138 x 185 cm. Parma, Fondazione Magnum Rocca. (158)

“Rest on the Flight into Egypt” (probably 1512). Oil on (paper laid down on) panel, 46.3 x 61,5 cm. Longleat, Wiltshire, Marquess of Bath Collection (stolen 6 January 1995). (161)

“Tobias and the Angel Raphael” (probably 1514). Oil on panel, 179 x 146 cm. Venice, Accademia. (167)

“Baptism of Christ” (probably 1514). Oil on panel, 115 x 89 cm. Rome, Museo Capitolino. (172)

“Noli Me Tangere” (probably 1514). Oil on canvas, 109 x 91 cm. London, National Gallery. (173)

“Sacred and Profane Love” (probably 1515). Oil on canvas, 118 x 279 cm. Rome, Galleria Borghese. (186)

Titian: "Noli Me Tangere"

Titian: "Noli Me Tangere"Joannides dealt with Titian’s portraits in a separate chapter but looking at the list above we must say that until Titian painted the “Sacred and Profane Love” in 1514-5, he was primarily a painter of “sacred” subjects.

The sole exception would be the controversial and mysterious “Pastoral Concert”: controversial because scholars still cannot agree on whether to give it to Titian or Giorgione, and mysterious because there is no agreement on the subject of the painting.

Moreover, Joannides noted Hourticq’s opinion that “although the ‘Concert’ was laid in by Titian around 1511, he completed it only around 1530…” He confessed that the temptation to accept Hourticq’s view is “considerable.” (p. 100)

In the five years after Giorgione’s death Titian became one of the greatest painters of the Renaissance but on the eve of the Reformation he and his patrons were still interested primarily in “sacred” subjects.

*Paul Joannides, "Titian to 1518" Yale,2001.