The annual

meeting of the College Art Association was held this year in New York City from

February 13 to 16. It was a huge conference with panels galore and an

incredible array of exhibitors. I

took the train down from Connecticut on Friday to have lunch with some other

Art history bloggers, and then to attend the panel entitled, “The New

Connoisseurship: A Conversation among Scholars, Curators, and Conservators.”

|

| Bloggers at lunch in NYC |

It turned out

to be a large panel featuring two chairpersons as well as six prestigious

presenters from high-powered institutions. Each presenter was slated to give a

ten-minute talk, and when all were done there would be a round table

discussion. The topic must be important since there were at least 200 people in

attendance in the huge West Ballroom of the Hilton hotel.

Chairperson Gail Feigenbaum opened

the proceedings with a mini overview of the concept of connoisseurship that

included a review of the reasons for its apparent decline despite her belief

that it was still “fundamentally indispensable.” She argued that the basic

concept was sound enough in that connoisseurship involves both expert knowledge

and an informed and discerning taste. However, the decline can be traced to a

number of factors.

Noted practitioners of the past

often were ignorant of or ignored scientific tools, and today scholars accuse

them of being unscientific, and question the value of mere “close

looking”. Moreover, there is still

a taint of corruption associated with connoisseurs like Bernhard Berenson who

worked very closely with art dealers and collectors. A favorable Berenson

opinion could substantially increase the market value of any work of art.

Finally, there was a kind of aristocratic aura surrounding the old

connoisseurship that offends modern sensibilities. Only the wealthy could

afford to dabble in Old Masters, or even think of traveling to Italy to view

them.

|

| Bernhard Berenson |

The first panelist was Maryan

Ainsworth, a distinguished scholar and curator of Renaissance painting at New

York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. She outlined some of the scientific

techniques that modern scholars are using to acquire expert knowledge. They

study fingerprints in books of Hours in order to assess popularity and usage.

Humidity stains are being examined in order to reconstruct old manuscripts.

Some are examining the canvas supports of paintings in order to verify the

proper placement of panels. Virtual restoration is now enabling scholars to

decipher illegible texts in old paintings, and therefore relate the texts more

closely to the subject of a painting. Students of Jan van Eyck are even using

painted pearls as a kind of digital signature. It would appear that they are

almost as good as a signature.

|

| VanEyck: Ghent Altarpiece detail |

David Bomfort,

a conservator at the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston, discussed the importance

of technical analysis of underpainting and paint samples in the new

connoisseurship. These scientific studies can produce what he called

“unambiguous information” that can

be helpful in questions of authentication and attribution. As an example, he

discussed Altdorfer’s, “Christ Taking Leave of His Mother,” as an example of

how technical analysis of pentimenti can help to construct the narrative. In a

similar vein E. Melanie Gifford of Washington’s National Gallery followed

Bomfort with a discussion of the use of pigment analysis in assessing the still

life’s of William van Aelst.

.jpg) |

| Altdorfer: Christ Taking Leave of His Mother |

Carmen C.

Bombach of New York’s Metropolitan Museum argued that the “new connoisseurship”

placed a much greater emphasis on drawings and preparatory sketches. In her

opinion the old connoisseurship tended to ignore or undervalue drawings and

concentrate almost exclusively on the finished product. Anyone aware of the

value placed on Renaissance drawings in the current art market would have to

agree with her.

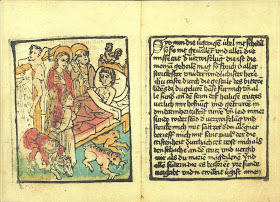

According to

Michelle Marincola of New York University’s Institute of Fine Arts,

reproductions of famous images are now seen by modern scholars as important

objects of study in themselves. In the old connoisseurship these reproductions

were largely ignored since they seemed to lose the power of the original cult

image. Marincola argued that now these reproductions, usually depicting the

Madonna and Child, can actually be seen as enhancing the prime image especially

if one takes into consideration the departures from the original in order to

satisfy varying devotional needs.

Elizabeth

Honig, an Art historian at the University of California at Berkeley, gave the

final presentation, “Oeuvre and the Internet, What Happens when People Stop

Using Our Books”. I believe that she was the first to raise the issue of the

Internet during the session. In the past her students would have to wade

through piles of catalogs and texts but now most of them merely turn to the

Web. For example, she pointed to sites devoted to Breughel and Vermeer that

were incredibly comprehensive. She acknowledged the problems associated with

Web scholarship but still believed that Art history would have to co-opt the

Internet.

It is true

that many scholars are reluctant to deal with the Internet. One noted Titian

scholar told me that he refused to read anything on the Web. Even young

scholars at the conference admitted that even if they blogged and used social

media, they would still not consider publishing their work on the Web. I

believe that it was Dr. Honig who ending her presentation by quoting another scholar, “the Internet is

an eight-lane highway but no one’s on it.”

Unfortunately,

I had to leave to catch the train before the round table discussion. On the

ride home I could not help but think that the “new connoisseurship” was not so

much different from the old. There is still a need for expert knowledge and

close looking and study are still valuable. Today’s scholars have more arrows

in their quiver, and the Internet has opened up the Art world to a much wider audience.

Nevertheless, the distinguished panelists at this session still were

representative of a kind of aristocracy of the Art world.

###