Old age and diminished eyesight have practically brought my art history career to an end. As a result, in 2023 I have decided to reproduce my various interpretive discoveries once again on giorgione et al... as a kind of archive. In the last month I have republished condensed versions of my interpretations of Giorgione's Tempest, as well as Titian's Sacred and Profane Love. Below find a third interpretive discovery that originally appeared here on October 11, 2011. The full paper can be found on academia.edu.

**************

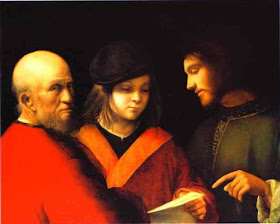

Giorgione’s Three Ages of Man is another one of his paintings that has so far eluded identification. The name of the painting that now hangs in the Pitti Palace is pure guesswork stemming only from the obvious disparity in ages of the three men. One appears to be about 60, another in his early thirties, and the last a young man in his teens.

|

| Giorgione: Three Ages of Man Pitti Palace, Florence Oil on wood, 62 cm x 77.5 cm |

Scholars today object to the popular title. Some think it represents a music lesson and that the man on the viewer’s right is pointing to musical notes on the paper held by the young man. Others claim that it represents the education of the young emperor/philosopher Marcus Aurelius. Others just throw up their hands and claim that it contains, like other Giorgione works, multiple levels of meaning.

However, the most spectacular element in this mysterious painting has so far received little notice. Venetian painters were known for their coloration. Just look at the garments of the three men. Nothing in a Renaissance painting is there by accident or whim. The colors in this painting provide a real clue to its subject.

As far as I know no one has suggested that the painting has a “sacred” subject, but yet, it appears that Giorgione has depicted a scene from the nineteenth chapter of the Gospel of St. Matthew. It is the story of the encounter of Jesus with the young man of great wealth. (See below for full text)

In Matthew’s account the young man asked Jesus what he could do to attain eternal life. Jesus told him to keep the Commandments, and specifically named the most important. The man replied that he had done so but still felt that something was wanting. Jesus then uttered the famous words, “If thou wilt be perfect, go, sell what thou hast, and give to the poor, and thou shalt have treasure in heaven; and come, follow me.” The gospel relates that the young man went away sad for he had many possessions.

How has Giorgione depicted this story and who is the third man? The man in the middle is obviously young and the golden lapels of his garment as well as his fashionable hat indicate that he is well to do. He is holding a piece of paper or parchment that contains some indecipherable writing that under magnification hardly looks like Renaissance musical notation.

On the right most Venetians would have immediately recognized the visage of Jesus. There is no halo or nimbus but Giorgione never employed that device. The pointed finger is certainly characteristic of Jesus. Here he points not at a sheet of music but at the Commandments, which the gospel account has just enumerated.

Jesus wears a green garment or vestment, certainly an unusual color for him. In fact, it looks like the robe or chasuble worn by a priest during Mass. At the hand of Jesus we can also see the white sleeve of the “alb", a long white robe always worn under the chasuble. Green is the color used by the Catholic Church during Ordinary time, that part of the Church year not identified with any of the great feasts.

The third man is St. Peter. He is the only other person identified in Matthew’s account of this incident. He stands on the left, head turned toward the viewer. Giorgione uses Peter as an interlocutor, a well-known Renaissance artistic device designed to draw the viewer into the painting and encourage emotional participation. The old man’s face is the traditional iconographical rendering of Peter with his baldhead and short stubby beard. As Anna Jameson noted many years ago, Peter is often portrayed as ”a robust old man, with a broad forehead, and rather coarse features.” **

|

| Durer: St. Peter detail |

|

| Caravaggio: Denial of Peter |

The color of Peter’s robe is also liturgically significant. Peter is rarely shown wearing red, but Giorgione has chosen to show him wearing the color reserved for the feast days of the martyrs. In the gospel account immediately after the young man went away sad, Peter, speaking for the other disciples as well as for the viewer of Giorgione’s painting, had asked, “Behold we have left all and followed thee: what then shall we have?”

In the first decade of the sixteenth century Venice was at the apex of its glory. It would suffer a great defeat at the end of the decade during the War of the League of Cambrai but until that time it was arguably the wealthiest and most powerful of all the European nations. It was certainly the only one that dared confront the mighty Ottoman Empire.

Nevertheless, some young Venetian patricians were wondering whether the whole life of politics, commercial rivalry, and warfare was worthwhile. One of them, Tommaso Giustiniani, a scion of one of the greatest families, did actually sell all his possessions, including his art collection, in order to live as a hermit in a Camaldolensian monastery. At one point he wrote to a few friends, who were also considering a similar move, about the futility of their daily lives. He argued that Venetian life was agitated, completely outward, and continually dominated by ambition. It was the reason for all their worry.

“If, then, a Stoic philosopher appeared to free their minds from all these disturbances, his efforts would be in vain, so completely does agitation dominate and enfetter their whole lives. How can anyone not feel disgust for such an empty existence.”? ***

Peter and the other disciples were shocked when Jesus said that it would be harder for a rich man to enter the kingdom of heaven, than for a camel to pass through the eye of a needle. “Who then can be saved,” they asked? The response of Jesus was full of hope: “With men this is impossible, but with God all things are possible.” Green, the liturgical color used throughout the Church year, is also the color of hope.

“The Encounter of Jesus with the Rich Young Man,” the name we can now give to the painting in the Pitti Palace, would certainly appear to have an historical context in Giorgione’s time. Five hundred years after the death of this short-lived genius perhaps we can begin to understand that Giorgione was a unique and original painter of sacred subjects.

###

Full text of Matthew 19:16-27.

And behold, a certain man came to him and said, “Good Master, what good work shall I do to have eternal life?” He said to him, “Why dost thou ask me about what is good? One there is who is good, and he is God. But if thou wilt enter into life, keep the commandments.” He said to him, “Which?” And Jesus said,

Thou shalt not kill,

Thou shalt not commit adultery,

Thou shalt not steal,

Thou shalt not bear false witness,

Honor thy father and mother, and,

Thou shalt love thy neighbor as thyself.”

The young man said to him, “All these I have kept; what is yet wanting to me?” Jesus said to him, “If thou wilt be perfect, go, sell what thou hast, and give to the poor, and thou shalt have treasure in heaven; and come, follow me.” But when the young man heard the saying, he went away sad, for he had great possessions.

But Jesus said to his disciples, “Amen I say to you, with difficulty will a rich man enter the kingdom of heaven. And further I say to you, it is easier for a camel to pass through the eye of a needle, than for a rich man to enter the kingdom of heaven.” The disciples hearing this, were exceedingly astonished, and said, “who then can be saved?” And looking upon them, Jesus said to them, “With men this is impossible, but with God all things are possible.”

Then Peter addressed him, saying, “Behold we have left all and followed thee: what then shall we have?”

* Note: This article first appeared in Giorgione et al... on Oct. 8, 2011. It followed upon my interpretations of Giorgione's Tempest, and Titian's Sacred and Profane Love as sacred subjects. The full papers can be found on my website, MyGiorgione.

** Anna Jameson, "Sacred and Legendary Art," Boston, 1896, Vol. 1, p. 191.

*** Dom Jean LeClercq, Camaldolese Extraordinary, The Life, Doctrine, and Rule of Blessed Paul Giustiniani, Bloomingdale, Ohio, 2003, pp. 61-62.