In the Age of Giorgione, currently on

exhibition at the Royal Academy of Arts in London, has attracted a lot of

attention in the British press. Questions of interpretation and attribution

have inevitably arisen, and some critics have complained that Giorgione is

hardly represented. The curators of the exhibition admit that “complex

questions of attribution” have always surrounded Giorgione and his work, but

argue that the current exhibition is really an attempt to explore Giorgione’s

world by featuring the works of a kind of brotherhood of artists working in

Venice in the first decade of the sixteenth century.

In the Age of Giorgione brings together works by a number of artists who lived in Venice at the time: Giovanni Bellini, Giorgione, Titian, Sebastiano del Piombo, Lorenzo Lotto and less well-known figures such as Giovanni Carianni among others. Through a consideration of the city’s artistic context at the turn of the century, this exhibition explores Giorgione’s visual identity in depth, examining how his significant contribution helped shaped the exciting new generation of artists.

Questions of

attribution are of great importance not only to art historians, dealers, and

collectors, but also to the general public. Museumgoers will flock to see a

genuine Raphael, but will show little interest in a similar Madonna by some

member of Raphael’s studio. However, I would like to argue that interpretation

of paintings matters more that attribution when it comes to understanding the

age of Giorgione.

A good example

can be found in a small pamphlet, “Exhibition in Focus,” that the Royal Academy

has produced for visitors. The exhibition has been divided into four sections:

Portraits, Landscape, Devotional Works, and Allegorical Portraits. In the

Allegorical Portrait section, devoted to “portraits of individuals depicted in

mythological or religious guises,” the curators discussed Cariani’s Judith, and Giorgione’s La Vecchia. They also believed that

Giorgione’s Three Ages of Man, which

apparently had not arrived from the Pitti Palace in time for the opening of the

exhibition, was an allegorical portrait representing the passage of time in its

depiction of three men of different ages.

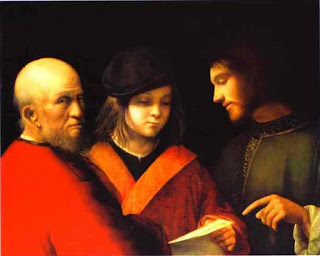

His Three Ages of Man, c. 1500, depicts a youthful boy flanked by a grown man and an older gentleman. The older man is looking over his shoulder at us, thereby establishing a direct connection with viewers. The painting is generally interpreted as an allegory of the three stages of life: boyhood, adulthood and old age. Like the old woman in La Vecchia, whose gaze gives that painting a startling immediacy, the three men depicted in this painting communicate its message with brutal honesty.

Nevertheless, I

have argued that the Three Ages of Man

is as much a devotional work as Titian’s Christ

and the Adulteress, and as such provides great insight into the world of

Giorgione and his contemporaries. Although it is usually called the Three Ages of Man because of the obvious

disparity in the ages of the men, scholars disagree on the subject or meaning

of this painting. Today, most reject the three ages label. Some call it a

“music lesson” while others prefer to see it as the education of a figure from

antiquity like Marcus Aurelius. But, once it is pointed out, I believe that any

ordinary person would be able to see that it is a depiction of the encounter of

Jesus with the rich young man from the nineteenth chapter of the gospel of St.

Matthew. Here is an excerpt from

my paper that can be found at my site, MyGiorgione.

In Matthew’s

account the young man asked Jesus what he could do to attain eternal life. Jesus told him to keep the

Commandments, and specifically named the most important. The man replied that

he had done so but still felt that something was wanting. Jesus then uttered

the famous words, “If

thou wilt be perfect, go, sell what thou hast, and give to the poor, and thou

shalt have treasure in heaven; and come, follow me.” The gospel relates that the young man went away sad for he had

many possessions.

How

has Giorgione depicted this story and who is the third man? The most spectacular elements in this mysterious painting are the colors of the garments of the three men. Nothing in a Renaissance painting is there by accident or whim. The colors in this painting provide a major clue to its real subject.

The man in

the middle is obviously young and the golden lapels of his garment as well as

his fashionable hat indicate that he is well to do. He is holding a piece of

paper or parchment that contains some indecipherable writing.

On the right,

despite the inability of art historians to see, any Christian, Venetian or

otherwise, would immediately recognize the visage of Jesus. There is no halo or

nimbus but Giorgione never employed that device. The pointed finger is

certainly characteristic of Jesus. Here he points at the Commandments, which

the gospel passage has just enumerated. Jesus wears a

green garment or vestment, certainly an unusual color for him. In fact, it

looks like the robe or chasuble worn by a priest during Mass. At the hand of

Jesus we can also see the white sleeve of the “alb,” a long white robe always

worn under the chasuble. Green is the color used by the Catholic Church during

Ordinary time, that part of the Church year not identified with any of the

great feasts.

The third man is

St. Peter. He is the only other person identified in Matthew’s account of this

incident. He stands on the left,

head turned toward the viewer. Giorgione uses Peter as an interlocutor, a

well-known Renaissance artistic device designed to draw the viewer into the

painting and encourage emotional participation. The old man’s face is the traditional iconographical

rendering of Peter with his baldhead and short stubby beard. Artists often portrayed Peter as a robust old man, with a broad

forehead, and coarse features.

The color of

Peter’s robe is also liturgically significant. Peter is rarely shown wearing

red, but Giorgione has chosen to show him wearing the color reserved for the

feast days of the martyrs. In the gospel account immediately after the young

man went away sad Peter, speaking for the other disciples as well as for the

viewer of Giorgione’s painting, had asked, “Behold we have left all

and followed thee: what then shall we have?”

In

the first decade of the 16th century Venice was at the apex of its

glory. It would suffer a great defeat at the end of the decade during the War

of the League of Cambrai but until that time it was arguably the wealthiest and

most powerful of all the European nations. It was certainly the only one that

dared confront the mighty Ottoman Empire.

Nevertheless,

some young Venetian patricians were wondering whether the whole life of

politics, commercial rivalry, and warfare was worthwhile. One of them, Tommaso

Giustiniani, a scion of one of the greatest families, did actually sell all his

possessions, including his art collection, in order to live as a hermit in a

Camaldolensian monastery. He had come to believe that Venetian life was

agitated, completely outward, and continually dominated by ambition.

Tommaso

Giustiniani and other rich young men like him could have been patrons and even

friends of Giorgione and Titian in the first decade of the sixteenth century.

The Encounter of Jesus with the Rich Young Man, the name we can now give to the

painting, is a window into their age.

I

like to think that another painting featured in the Royal Academy exhibition

might portray Tommaso Giustiniani. It is the Giustiniani Portrait, a portrait of a young man who has become the

poster boy for the whole exhibition. I know that it is impossible to prove a

connection, but the painting was originally in the possession of a branch of

the Giustinani family, one of the great Venetian Patrician families.

|

| Giorgione: Giustiniani Portrait |

###