This year on Giorgione et al... I have been reprising my interpretive discoveries on Giorgione and other Renaissance masters. I am not the first to claim that the three men in the so-called Three Philosophers are the Magi, but I believe I am the first to point out the significance of the colors of their garments. My first post on the subject was back on 9/20/2010, and the post below is an update from 11/18/2018.

***************************

The Giorgione painting known as The Three Philosophers is one of a handful now definitively attributed to the great Venetian Renaissance master. It depicts three men on a hilltop overlooking a beautiful valley with the sun setting in the West behind a range of mountains. They are dressed in colorful robes and face a dark rock formation or cave. They and the cave are illuminated by another source of light. Who are they and what are they doing there?

In 1525 Marcantonio Michiel, a Venetian patrician and connoisseur, listed the paintings in the collection of Taddeo Contarini, another Venetian aristocrat, and described this one as "three philosophers in a Landscape." Two hundred and fifty years later the painting had found its way to the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, its current home. In a 1783 catalog it was called, "Three Magi." Since then, scholars have debated whether the men are philosophers, astronomers, surveyors, representatives of the three ages of man, representatives of three religions, or the Wise Men or Magi of the Biblical account.

Today, most scholars accept the "philosopher" interpretation even though they find it difficult to identify which ones. However, recent findings suggest that the Magi are making a comeback.

In the catalog of the unprecedented Giorgione exhibition in 2004, Mino Gabriele argued that in this painting Giorgione depicted the Magi not at the end of their journey but at the beginning, when they first saw the Star of Bethlehem. His most compelling point had to do with the lighting of the painting. If we look carefully, we can see the sun setting in the West behind the mountains, but the three men and the rock formation in the foreground are being illuminated by another source. According to the medieval legend the light of the Star, which rose in the East, was even brighter than the sun at midday. *

Moreover, at the conclusion of a symposium, that ended the “Bellini, Giorgione, Titian” exhibition at the National Gallery in Washington in 2006, Salvatore Settis offered a striking piece of evidence in support of the Magi.

The exhibition itself had done an excellent job of educating the public on the value of using scientific techniques to evaluate the "underpainting" of some of these Renaissance masterpieces. X-rays and other techniques show many "pentimenti" or changes of mind on the part of the artists. When working with oils, the artists would frequently alter their paintings by painting over the original.

In the original version the old man on the right dressed in gold is wearing an elaborate headpiece crowned with a kind of solar disk. For some reason Giorgione decided to discard it in favor of a simple hood. Nevertheless, when Settis projected an image on a huge screen of a painting by Vittore Carpaccio of the Magi on horseback approaching the Holy Family, the old man in that painting was wearing the kind of headpiece discarded by Giorgione.

|

| Carpaccio: Holy Family with Magi in Background detail provided by Dr. Settis |

In a 2010 post at Giorgione et al… I added my two cents to the question and argued that the colors of the garments of the three men are symbolic of the gifts of the Magi: gold, frankincense, and myrrh. The most obvious, but usually overlooked, feature in the painting is the brilliant color of the costumes. In the medieval legend, the oldest of the Magi was the bearer of the gold; the middle-aged man carried the myrrh; and the youngest brought the frankincense. The golden garment of the oldest man needs no explanation. In my encyclopedia the color of myrrh is a dark red, while the color of frankincense can be white or green, the colors of the clothing of the sitting young man.

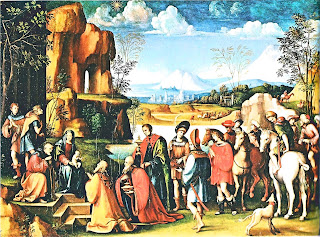

In other versions of the Adoration of the Magi, gold is almost invariably the color of the oldest man’s garb, but there is no one color scheme for the other two. However, there is a version of the Adoration of the Magi done around 1499 by Francesco Raibolini, known all over Italy as Francia, where he used a similar color scheme for the three Magi. In Francia’s painting, that I believe is now in the Dresden Gemaldegalerie, the eldest man is clothed in gold, the middle-aged one in red, and the youngest in green.

|

| Francia: Adoration of the Magi |

I also believe that The Three Philosophers was not the only instance in which Giorgione used colors symbolically to identify his religious figures rather than resorting to stock symbols. In the so-called Three Ages of Man, that now hangs in the Pitti Palace, the colors of the garments of the three men are more than enough to identify them. St. Peter, in particular, is identified by his bright red robe; red being the color of martyrdom. The green of Christ’s garment is the color of the vestment used by a priest during most of the liturgical year, and the purple and gold of the young man are a sign of his wealth.

Giorgione also used red for the tunic of the young man in the so-called Boy with an Arrow. Red should help to identify this mysterious figure holding an arrow as the martyr, St. Sebastian. **

Perhaps Giorgione, Carpaccio and Francia took their inspiration from the elaborate public processions honoring the Magi, which were common in the later Medieval world. Nowhere were they more elaborate than in Venice. More than any other city, Venice was aware of the styles and costumes of the Orient.

Could it be that Giorgione hid his subject by making it obvious? I think it more likely that most contemporary Venetians would have seen the Magi in this great masterpiece.

###

*Mino Gabriele, “The Three Philosophers”, the Magi and the Nocturnal.” Giorgione, Myth and Enigma, ed. Sylvia Ferino-Pagden and Giovanna Nepi Scire, 2004. Pp.79-85.

** Discussions of both of these Giorgione paintings have already been posted this year on this site.

Addendum:

Credit must be given here to Anna Jameson, the popular British art maven of the nineteenth century. Neglected today by most art historians, I believe that she was one of the few who worked to restore the original meaning and significance of Medieval and Renaissance art from the ignorance of the Enlightenment. In her discussion of the Adoration of the Magi she paused to discuss Giorgione’s painting.

I must mention a picture by Giorgione in the Belvedere Gallery, well known as one of the few undoubted productions of that rare and fascinating painter, and often referred to because of its beauty. Its significance has hitherto escaped all writers on art, as far as I am acquainted with them, and has been dismissed as one of his enigmatical allegories. It is called in German, Die Feldmasser (the Land Surveyors), and sometimes styled in English the Geometricians, or the Philosophers, or the Astrologers. …I have myself no doubt that this beautiful picture represents the “three wise men of the East,” watching on the Chaldean hills the appearance of the miraculous star, and that the light breaking in the far horizon, called in the German description, the rising sun, is intended to express the rising of the star of Jacob.” #

In a footnote, Jameson mentioned a print by Giulio Bonasoni, “which appears to represent the wise men watching for the star.”

#Anna Brownell Jameson, Legends of the Madonna, as Represented in the Fine Arts, Boston and New York, 1885, pp. 347-8.